While dealing with transmission of medieval stories in extant manuscripts, book historians and textual scholars face the common problem, that the sample of materials that survived to our times is only a fraction of what once existed. By examining library catalogues and lists of books, together with analysis of references to lost works, scholars have been trying to estimate the extent of the loss. The recent study published in Science, with Mike Kestemont (University of Antwerp) and Folgert Karsdorp (KNAW Meertens Institute) as the main authors and myself as one of the contributing authors, applied statistical approaches borrowed from ecology, to tackle the same problem.

It was a great pleasure to collaborate with scholars from various disciplines and academic traditions to bring this innovative project to completion and contribute my perspectives on the Icelandic rímur tradition. As Carlsberg Foundation JRF at Linacre, I focus on book historical approaches to transmission and reception of Old Norse-Icelandic literature, while in my previous work I studied a lost medieval saga, which has not survived in its original form, but exists in multiple younger adaptations in prose and verse. Thus, the research questions leading our collaborative study carry direct implications for my own work.

By using statistical methods borrowed from ecology, we were able to add to previous scholarship and estimate that more than 90% of medieval manuscripts preserving chivalric and heroic narratives have been lost. Moreover, we were able to estimate that some 32% of chivalric and heroic works from the Middle Ages have also been lost over the centuries.

Our team used the ‘unseen species models’ from ecology to gauge the loss of narratives from medieval Europe, such as romances about King Arthur, or heroic legends about Sigurður the Dragon Slayer or the legendary ruler Ragnar lóðbrok, known to wider audiences from the TV series Vikings. We observed significant differences in survival rates for medieval works and manuscripts in different languages, suggesting that the Irish tradition of medieval narrative fiction is best preserved, while works in English suffered the most severe losses. We calculated that around 81% of medieval Irish romances and adventure tales survive today, compared to only 38% of similar works in English. Similarly, results suggest that around 19% of medieval Irish manuscripts survive, compared to only 7% of English examples.

Icelandic, which is my area of expertise, is among the languages that were more resistant to loss, as according to our estimates it preserved 77% of works of narrative fiction and 17% of manuscripts. From the previous scholarship, it can be concluded we know around 68% of the works of the Old Norse-Icelandic legendary sagas – dealing with the adventures of Scandinavian heroes such as Sigurður or Ragnar lóðbrok. Similarly, if we look at the catalogue of Icelandic rímur, metrical romances dating from both medieval and postmedieval periods, we can estimate the survival rate of around 77%. Taking into consideration that the method we’ve applied in our study is giving a lower bound for loss, our estimated 77% survival rate for medieval Icelandic narrative fiction seems to be pretty promising.

Our research has also revealed interesting similarities between Icelandic and Irish traditions. Icelandic and Irish literatures not only have high survival rates for medieval works and manuscripts, but also very similar “evenness profiles”. Evenness is a term we again borrowed from ecology. In our case, this means the average number of manuscripts that preserve medieval works is more evenly distributed than in other traditions we examined. This is a very intriguing finding because island ecosystems are known to be better at preserving their biological diversity, so it’s an interesting hypothesis to entertain whether the same patterns could facilitate better survival of cultural heritage in those island societies. Recently, similarities between Irish and Icelandic manuscript cultures have been increasingly attracting scholarly attention and our research results definitely generate further questions.

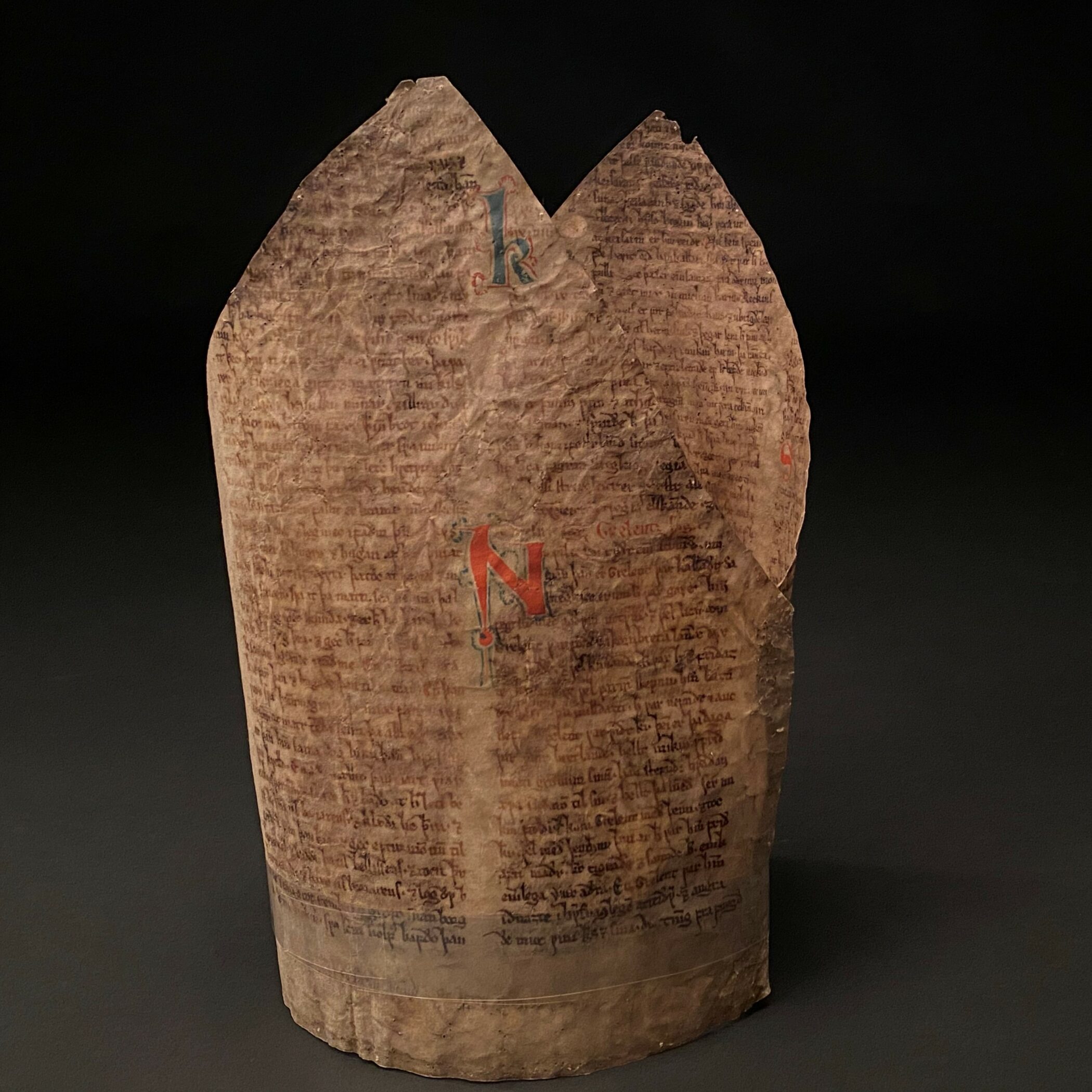

The similarities between Iceland and Ireland may be caused by lasting traditions of copying literary texts by hand long after the invention of print. The printing press arrived in Iceland in the late sixteenth century and for two hundred years (until the late eighteenth century) the only printing press was owned by the bishopric in Hólar in Northern Iceland. This meant that only text that were valuable enough from the perspective of the church were printed. The entertaining literature, as heroic narratives and romances, remained copied by hand through the entire early modern period. Thus, Icelandic audiences were used to the manuscript medium as an active medium for text circulation and perhaps because of this, more medieval manuscripts survived. Another explanation might lay in the modes of production of Icelandic literature in the Middle Ages. In our data-set most manuscripts are multi-text codices, meaning that usually two or more stories appear in the same book. Perhaps the co-occurrence of texts in manuscripts influences the chances for their preservation. This is something that would be very interesting for us to explore further in the future.

Dr Katarzyna Anna Kapitan (Carlsberg JRF)

Dr Katarzyna Anna Kapitan’s research project Virtual Library of Torfæus hosted at Linacre is funded by the Carlsberg Foundation.

Author Explanation Video

Project webpage

Article

Oxford University Press Release