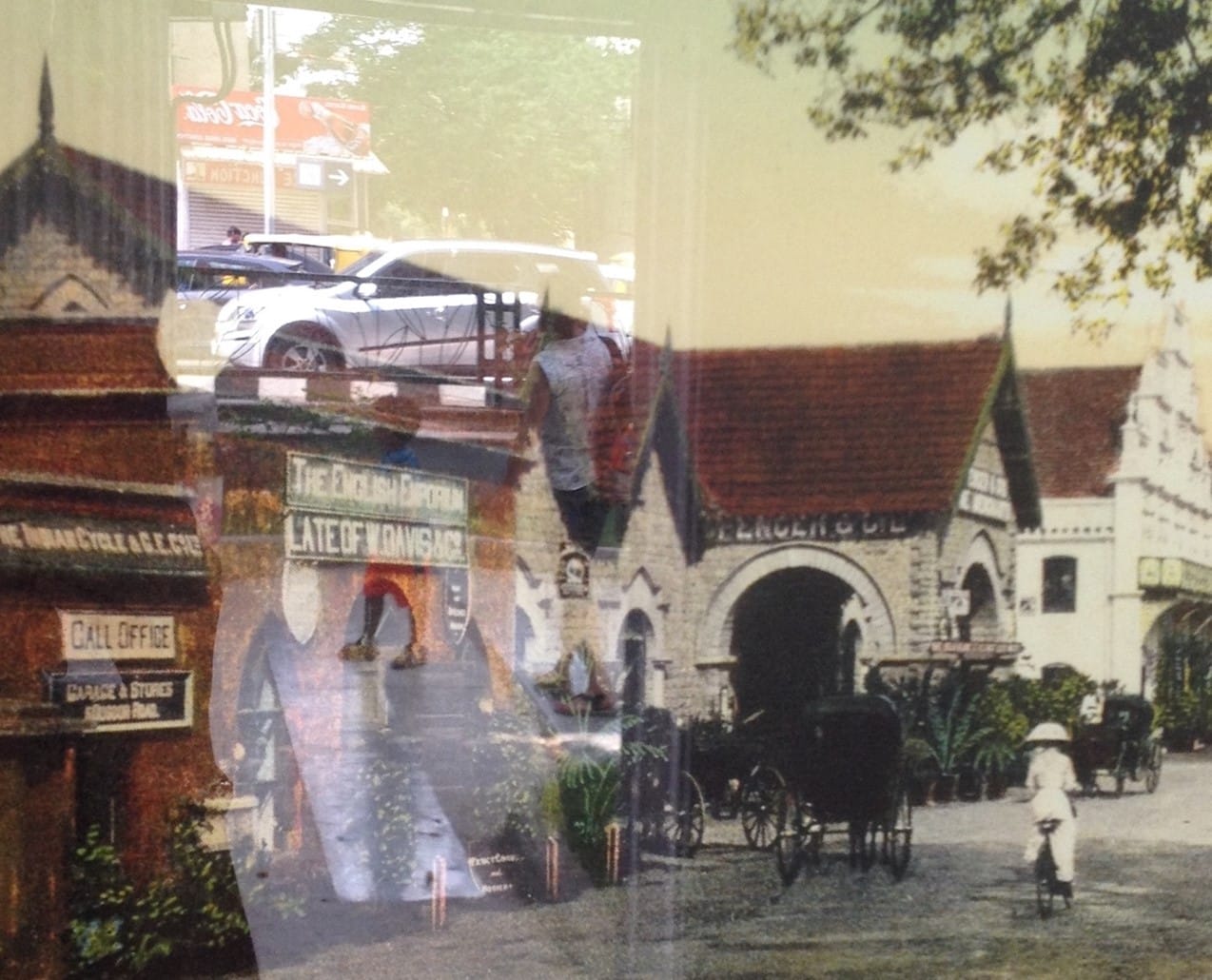

In the early twentieth century picture postcards of India were circulated around the world in immense numbers as an innovative new medium that combined mass-reproduced photographs with personal messages – not unlike social media of today. Whilst having often been dismissed as low-value ephemera, these small photographic items were produced through complex, global processes that involved numerous individuals, technologies, and materials. Once purchased, their social lives continued as they were written and posted to friends and family, shared through collection networks, and carefully curated into albums. As such, picture postcards tell countless stories and provide unique insights into the history of photography, and the visual and everyday politics of colonialism. However, far from having disappeared, countless such picture postcards continue to circulate in the present as they are collected, reproduced, digitised, and displayed.

Whilst conducting my doctoral research in Bengaluru, India, I followed picture postcards into photo studios, galleries, public spaces, and private collections, on heritage walks, and online. I spoke with and got to know the descendants of photographers who produced postcards in the early 1900s, avid collectors who weave them into personal and collective stories of their city, heritage enthusiasts who use their images for historical research, and artists who take inspiration from this visual and material “archive” of the colonial past. I have also spent multiple years tracing the individuals and studios who were involved in producing picture postcards of Bengaluru in the early 1900s (then Bangalore), including through archival research at the Karnataka State Archives and the British Library, and have slowly accumulated my own collection of postcards. It is this ethnographic and archival research that forms the basis of my book, ‘British Indian Picture Postcards in Bengaluru: Ephemeral Entanglements’.

Known as the “IT capital of India,” Bengaluru has experienced intense, rapid, and often unplanned urbanisation since the late twentieth century that has dramatically altered the social, physical, and economic landscape of the city and, according to many long-term residents, has occluded the city’s other identities and pasts. Whilst in the early 1900s the city’s population was less than 200,000, by 2001 it had reached close to 5.7 million. In the first decade of the twenty-first century the urban growth rate was over 46 percent and it is now one of the largest and fastest growing cities in India. In Ephemeral Entanglements, I show that the social lives of colonial-period postcards stretch from their initial production and consumption in the early 1900s into the present where they act as visual and material mediators in productions of historical imagination against this backdrop of intense urbanisation.

Weaving together the voices of photographers, collectors, heritage enthusiasts, and long-term residents of the city with archival material and picture postcards themselves, I have explored how picture postcards, as a more accessible visual archive of the colonial past, entangle with people, discourses, things, and places in shifting, and at times frictious, ways.

Whilst the production of postcards in the early twentieth century involved both Indian and European photographers, business owners, apprentices, and artists, they were overwhelmingly marketed to and consumed by Europeans and as such were intimately implicated in the politics and discourses of colonialism. For the collectors in Bengaluru who shared their experiences, knowledge, and picture postcards with me so generously, I found that their collections elicit multiple remembrances and discourses that speak to critiques of colonialism as well as to personal histories and nostalgia for their city’s pasts.

Outside of private collections, the remediation of picture postcards reveals the complex ways in which heritage, locality, and history are produced in Bengaluru through on-the-ground ephemeral entanglements. I discovered an unfolding four-part narrative of one particular postcard collection that can either be read as introductions to the following chapters of the book or as a stand-alone, parallel ethnographic story.

Currently owned by Ganesh and Hemamalini, since the early 1900s this particular box of postcards has changed ownership and value, moved between different localities in Bengaluru, and accumulated multiple marks of use, traces of dust, and creases in their corners. In the process, the postcards have accumulated different meanings, forged shifting social relationships, and been linked to broader local and national processes throughout the twentieth century such as migration and urban change.

My current research as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow and Linacre JRF, entitled Studio Encounters, continues to address similar themes by examining commercial photo studios as sites of encounter in the colonial South Indian city, and the ways in which local photographic histories are produced, remembered, and narrated in the present. Through a combination of ethnographic, archival, and digital methods my research therefore explores questions of locality and heritage production, urban change, and colonial history in relation to everyday forms of visual media.

For further details: British Indian Picture Postcards in Bengaluru: Ephemeral Entanglements

[1] See; Smriti Srinivas, Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and the Civic in India’s High-Tech City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 47; Janaki Nair, The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 79; and John C. Stallmeyer, Building Bangalore: Architecture and Urban Transformation in India’s Silicon Valley (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), 37.