If one wanted to pinpoint the start of my research journey at Oxford, one could turn to two dates: mid-march a year ago and around the same calendar but one hundred and seventy-five years in the past, both near St. Louis, Missouri.

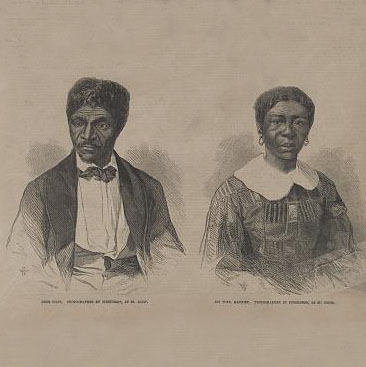

On April 6, 1846, two enslaved African-Americans, Dred and Harriet Scott, filed suit at the local courthouse in St. Louis, asking for the court to grant them liberation. To contemporary ears, this might sound unusual, but even though Missouri was a slave society, it had a procedure in place by which enslaved individuals could challenge the legal ownership of their bodies by their enslaver. Of course, for those suffering in bondage, pursuing freedom this way was no easy task. But hundreds attempted in the antebellum period, many successfully, a testament to their will to survive and overcome the exploitative system of chattel slavery in America.

As these suits reached the courts, three bases coalesced by which a judge, with a fact-finding jury, could grant petitioners liberation. Perhaps the most interesting among them, and the one central to the Scotts’ suit, was emancipation-by-residency. In such a case, liberation would rest on whether the putative slaveowner had taken the enslaved petitioner to a free jurisdiction – where slavery was illegal – for purposes of residency or work. In the decades prior to the Scotts’ suit, the Missouri Supreme Court fostered a liberal jurisprudence that expanded the circumstances of this basis. For example, the Court removed the intention of the slaveowner to establish residency as a necessary condition; in one case, a slaveowner’s purposeful leaving of his traveling wagon packed to express an intention of merely sojourning through a free state was not enough to prevent the forfeiture of his ownership rights to the enslaved Daniel Wilson. In fact, the Scotts seemed very favorable to win their freedom, with an enslaved woman named Rachael having won her liberation in almost exactly the same circumstances a few years earlier. Thus, it must have been heartbreaking that, in their very case on appeal after years of litigation in 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court abrogated decades of precedent to rule against them. Such a setback was not only catastrophic for them, but as Missouri followed the partus sequitur ventrem doctrine, where the status of a child followed that of the mother, Dred and Harriet knew their daughters’ fate hung in the balance as well.

A year ago, nearly 174 years after the Scotts filed their initial suit, I had an opportunity to present my master’s research at a conference outside of St. Louis. This was an auspicious venue, in both time and space, as my talk was on this antebellum Missouri state caselaw leading to the Dred Scott case (Harriet’s separate suit subsumed into her husband Dred’s). My thesis: though the Court had enlarged the circumstances by which enslaved individuals could emancipate themselves through these suits, its jurisprudential reasoning actually served to diminish the personhood of the enslaved, underpinning this basis in the more fluid interstate relations of comity. In other words, there was rust underneath this “golden era of freedom suits” that would allow a later Court in the Scotts’ case to overturn everything, the caselaw and Scotts’ hope of freedom in the state courts.

However, the Scotts’ legal journey did not end in Missouri; after the state courts failed them, they started again, turning to the federal circuit. This eventually led them to the United States Supreme Court where Chief Justice Roger Taney rejected the Scotts’ claim in perhaps the Court’s most infamous ruling, declaring, among other things, that enslaved African-Americans and their descendants could not be citizens because they did not belong among the ‘People’ of the United States. My research follows the Scotts to the Supreme Court, taking the lessons of the state caselaw to look beneath the murk of Taney’s convoluted reasoning.

Though life may appear short to a historian, that presentation outside St. Louis last year seems so long ago, whereas Dred and Harriet’s suit feels so recent. Back at the conference, the hallway talk was about the first reported incidence in the region of a novel infection said to have emanated from Wuhan in China. Its strangeness seemed to animate everyone, myself no exception, but my attention was soon stolen by other exciting news: awaiting for me back in my lodgings was an invitation to join Linacre’s community. So much uncertainty, but so much promise. Since that presentation, and coming to Oxford, I have become more familiar with confined spaces – the lonely airplane, the empty bus, the lockdown room – but my intellectual pursuits knows no such bounds. With the recent solitude and the resources provided by Oxford and Linacre, including the Rothermere American Institute a quick jaunt down South Parks Road, I’ve had the opportunity to reach outside my discipline, for example to Queer Studies, Animal Studies, and Literature Analysis, for new insights on the Dred Scott case. And with new light, I have been drawn to how Taney’s reasoning seems to speak of community as a binary, of those belonging with rights and those outside with none; an attempt to other African-Americans into perpetual subservience rests on a notion that the other ought to be diminished.

These insights offer lessons for modern society, one still reeling in the shadows of the forces that generated the Dred Scott decision in the first place. Some are fairly obvious, and activists of racial justice have labored hard to bring them to the public’s often blinded attention. But this idea of community and othering also appears in more inconspicuous ways. For example, with Covid-19 (the last time I should mention this unpleasantness) it is interesting that the coronavirus is portrayed as some vile enemy, with society at war against it, NHS workers described as soldiers fighting the good fight. Yet, it is strange that, for an enemy, it has shown no animus towards humankind, at least that I am aware, and it is a shame the coronavirus cannot live like the other microscopic forms of life that co-exist with the human body. None of this is meant to diminish the harm nor the noble cause of those attempting to save lives and ease suffering. But the fact that this is the way disasters are conceptualized, in forms of community and othering, is telling. And while the coronavirus is unlikely to be insulted, the same mechanism might be taken up against people, as has been the case countless times in the past. I am unsure where this intellectual journey will take me, but this process of othering is something I’ve been thinking about deeply since I received my invitation to join the Linacre Community at that auspicious conference a year so long ago.

Jacob Brandler (2020)

DPhil candidate in History