Cherwell Edge was originally built as a house in 1886 to 1887, with private tenants until 1904 when it was taken over by the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, or SHCJ, who rented the building from Merton College to use for boarders. Cherwell Edge was a part of the Society for Oxford Home Students, which later became St. Anne’s College.

The SHCJ hostel provided ‘Catholic surroundings and a Catholic atmosphere’ for young female Catholic Oxford students ‘while leading in every detail the life of the ordinary college-girl’. In 1907, with the permission of Merton College, the SHCJ added two wings to the building to accommodate the growing number of boarders and to provide a chapel. The name of the convent was St. Frideswide’s.

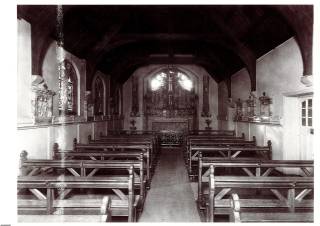

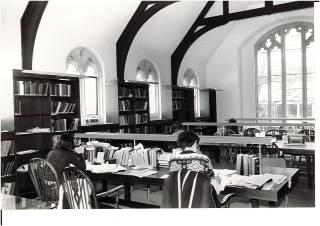

During the time that Cherwell Edge housed St. Frideswide’s, what is now the Nadel Room at Linacre functioned as the library for the sisters. What is now our library was, at this time, the convent’s chapel and the shape of the space and windows retain an echo of this former purpose. As a self-confessed bibliophile it is tempting for me here to draw upon romantic notions of a link between a chapel and a library as a place of worship, one of faith and one of knowledge like Sartre viewing the library as temple, and while this may seem fanciful, the fact that so many of Oxford’s colleges have libraries transformed from chapels suggests a connection between them deeper simply than an efficient use of space.

In addition to the architectural history of the library, I take a particular interest in the history of its use and contents, and the materials we have in the College archives have provided an insight into the thoughts and desires for the library, of both its users and librarians, in the past. In a suggestions book from the Linacre library while still at the St. Aldate’s site, I have found some comments which feel especially pertinent to the library’s interests today, with the ongoing collection development project of our librarians. One suggestion from the 17th of November 1971 recommends that the library acquires Mirella Ricciardi’s Vanishing Africa, a book published that same year, which the student writes is “The sort of book no-one could afford to buy for himself but would love to read and look at”. They say it is “surely the right thing for the library… Very well reviewed from the point of view of commentary and photography – of vanishing tribal people of Africa”. Another suggestion a few months later came from a student requesting Michael Banton’s 1967 work Race Relations, writing that “We have nothing on race relations in the library – this is a good basic introduction to the subject”. Fortunately we can confidently say that concurrent with the growth of scholarship and access to studying such topics, the library does now hold a much stronger collection to reflect the diversity of Linacre’s research backgrounds and interests, but the parallel in intentions between the 1970s and today to further diversify, decolonise and progress the library highlights the defining characteristics of Linacre and Linacrites which have been present since the earliest days: an interest in crossing national, cultural and disciplinary boundaries, and a commitment to forward-thinking.

In 1969, after years of providing both a spiritual and physical home to Catholic women studying for Oxford degrees, it was decided that Cherwell Edge was no longer the most suitable building for the work of the SHCJ in Oxford (and the University were very keen to take ownership and use of the site) and the community moved to 14-16 Norham Gardens.

During the building transformation from chapel to library ahead of Linacre’s move into Cherwell Edge, the stained glass was misplaced by the construction company. This was replaced by some alternative coloured glass to apologise, and central panes with Linacre emblems were made to complement this, although this was never installed in the library and it remains in storage in the College archives. The library team have been thinking about options to display this glass in the home it was intended for; perhaps we will see it on display in the library one day.

As all librarians are aware today, the increasingly digital world throws into question the future use of libraries, most obviously the use of physical books, but also their spatial functions more generally. Academic study is not immune to wider cultural shifts and trends, so what is most important for everyone’s benefit is that institutions and facilities adapt to changing times. Amusing to us now that we have expectations of plug sockets and wifi at all desk spaces, a letter from Linacre’s first Librarian, the late Giles Barber, to Jon Bamborough in the 1960s states that he was “a little worried about a typing room”. He notes that “the present trend is for a terrific demand for this – Bodley, B.M., St. Antony’s, all round and especially with Americans who can’t write long hand. Clearly they should not type in the library – but would it be possible to switch the room opposite to “Tutorial-or-Typing” Room? So much will depend on their habits evidently but I feel that this might well be a draw”.

Almost in reply, a response from our most recent annual student satisfaction survey asks pointedly, “Are libraries relics of pre-internet eras?”. Such discourse generates laughter for those of us so acutely aware of the beneficial functions of a library but as Giles ultimately saw in his own hesitations, compromise between present and future needs is how the space can serve its users most satisfactorily. While some of our current students may wish to replace the library with a coffee shop, the vast majority are incredibly grateful for the comfortable, quiet and productive environment for their studies, even though it may now be called one big Typing Room.

Pictured from left to right: The original Chapel that now houses Linacre Library, the Library in the 1970s, Linacre librarians from the 1970s to present day

Article written by Amy Wells

[1]https://www.shcj.org/the-shcjs-121-years-in-oxford-england/, Accessed July 2023